![]() IMMUNOLOGY LABORATORY >> BIological Principles

IMMUNOLOGY LABORATORY >> BIological Principles

The immune system is an integrated arrangement of cells, organs and structural elements, which are directed at the provision of a range of defence mechanisms for the body. A properly functioning immune system provides various methods of dealing with invasion by bacteria, viruses and other micro-organisms as well as a highly effective means of eliminating those cells within the body that might have become injured or defective (for example cancer cells), or that are not recognized as being a normal part of the body (for example a transplanted organ).

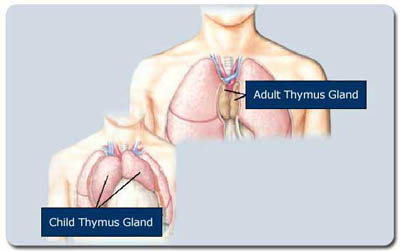

Adult & Child Thymus Comparison

The importance of the thymus gland to the function of the immune system has been well documented and is underpinned by the correlation between the susceptibility to infections, and the subsequent very short life spans, of animals and humans born with congenital defects in thymus development. The thymus is the primary site in the body where T cell development occurs. The thymus itself is a multi-lobed organ located inside the chest cavity, nestled tightly between the lungs just above the heart. It can be found early during development of the embryo in utero and continues to grow during childhood reaching a maximum size before puberty. The thymus weighs around 30-35 grams at its youthful maximum and thereafter shrinks post-puberty by up to 80 percent in mass. Furthermore, of the remaining tissue the vast majority is fatty tissue which is incapable of making T cells.

It was once believed that adults developed their entire, life-long complement of T cells (with the full repertoire of specificities) before the onset of puberty, and that after puberty the thymus underwent atrophy with no, or extremely limited, further T cell development happening thereafter.

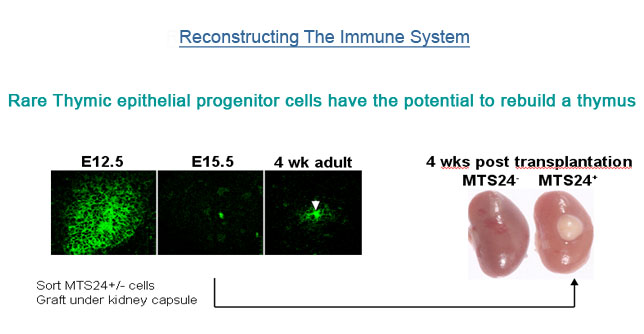

The Boyd Laboratory and others have demonstrated that the adult thymic remnant continues to produce new T cells, but on a significantly reduced scale – only a few percent of its former, pre-pubertal output. However, despite such low output, the thymus retains the capacity to produce new T cells, indicating that all the necessary elements for T cell differentiation remain intact even in the adult.

The association of thymic atrophy and decreased T cell production with increasing age, particularly from puberty, suggested a causal link with sex steroids in this degenerative process. Accordingly the Boyd group have shown that the use or GnRH analogues to block sex steroids leads to increased thymus function, re-igniting the residual thymic remnant. The loss of sex steroids also improves the function of pre-existing T cells

GnRH Analogues

Fortunately, a reversible, non-surgical drug-based alternative to surgical castration exists today in the form of GnRH analogues.

The GnRH analogue treatments are intended to induce a temporary reduction in sex steroid levels in order to increase the size and output of the thymus, and elevate naïve T cell numbers in the periphery. On cessation of drug treatment, sex steroid levels return to normal, but the clinical benefits of an increased T cell repertoire in the periphery are retained. This transient effect provides a more acceptable alternative to the more permanent surgical procedures, and more than 25 years of clinical experience with this class of drugs in the treatment of prostate cancer has shown that this is associated with minimal side effects.

The effects of sex steroid ablation on the thymus are dramatically demonstrated in the figure below. The observed thymic re-growth, in the old, GnRH treated animal, begins within days of sex hormone removal and is complete by 2 to 4 weeks.